- Home

- Billie Kelgren

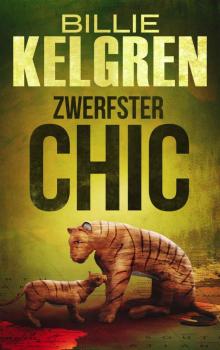

Zwerfster Chic Page 6

Zwerfster Chic Read online

Page 6

“I try,” is all Mia says, coming over to hold a light-gray silk blouse against the wool-silk blend of the pinstripe. It’s as if I’m some giant doll and these two girls are playing “dress up.”

Lilli’s hand then slides quickly up the inside of my thigh, knife edging my crotch before following the line between my cheeks. That is enough. I step off the platform and turn on her and she looks down at me in surprise. She laughs, telling Mia that I’m verlegen. Shy.

Fuck, yes, I’m shy when you do stuff like that.

Bokkie, Mia calls to me with a tone that’s telling me to grow up. I reluctantly climb back up onto the platform to allow Lilli to ravage me some more, but only after I stomp my foot in protest, so I guess the tone isn’t uncalled for.

When she’s done, Lilli looks at both me and my reflection in the mirrors, obviously proud of what she has accomplished given what she had to start with, which she described as zwerfster chic. Zwerfster wasn’t a word I was familiar with — a Dutch term for “bag lady.”

Now she tugs on one of the legs of the trousers, telling me to take them off. I look at her in the mirror, then step down off the platform again as she repeats herself in English, adding, “Don’t be so inhibited, nuku. I love the body of women.”

Okay, is that supposed to put me at ease?

Not this body of this woman.

I disappear behind a curtain while Mia comes over and quietly explains things to Lilli.

“Jesus, your face is messed up,” Tonya told me when we finally found one another at South Station, after I was released from prison. Only a sister can say something like that and have you think it wasn’t meant in a mean way. Like when she was eleven and I was fifteen and she pointed out that her boobs were already bigger than mine.

You see, I inherited my boobs from Ma and I still get embarrassed when I tell people that I’m a B because I’m really only kidding myself. I have her narrow nose, her thin lips, her small boobs, and her big butt. All that Dad seemed to give me was his black. Tonya, on the other hand, got her boobs from Mom, or maybe the one side of Dad’s family — Auntie Henrietta and her daughters, where they were all out of As before they were out of middle school. Naddie was the same way, though it would be a couple of years before we could tell, and by then I was out of the house, at college, so I was spared the humiliation.

I don’t think Naddie would’ve made anything of it, but Tonya never really forgave me for taking away her position as oldest daughter, so she was always quick to point out the ways that she was more mature than me, both mentally and physically. I wouldn’t be surprised to find out that she went to Harvard just to show me up.

We leave Lilli to her work on two suits: a black pinstripe and a brown plaid. (A tiny plaid, not the old traveling salesman kind of suit.) We have a late lunch at a café that overlooks the Prinsengracht canal and then sit in a nearby park while Mia tells me what she loves about Amsterdam, one of her favorite cities. She says she comes there three or four times a year and I ask her why she travels at all. What does she do that she can’t do over the phone, or on the internet?

Connecting, she says.

Even I’ve heard about Facebook. Some of the women in prison talked about family members who set up Facebook pages to keep friends and loved ones informed about what was happening with the dearly incarcerated. Thinking back, though, most of those women were white. Is Facebook a white thing? I don’t know. Mom never said anything about it, but then she’s never been all that big into technology anyway.

But I’m also not stupid. I don’t for a second think that Mia would use something as pedestrian as Facebook for illicit purposes. Still, I want to keep her talking because I feel like I’m beginning to understand what is going on.

“Then the word I’m actually looking for is influencing,” she says. “Influence is more about tone and body language than anything else. Not only your own, but also of the person you’re speaking with. You have to see what they’re thinking, what they’re feeling. You can’t do that over the phone or some webcam. At least, not as well as you can in person.”

I think about it a moment, trying to formulate a response that won’t make me come across as ill-informed. I don’t feel like sounding stupid to her at the moment.

“So you want to make sure they understand what you’re trying to tell them,” I say, to which she smiles and looks upon me with gentle patience. It’s as if she’s a mother trying to explain how planes fly to a four-year old.

“Actually, most of the time, I’m wanting them to mis-understand. It’s the difference between making millions and tens of millions.”

I think better of asking anything more because I’m certain I’m reaching the level of my own incompetence.

There are no stupid questions, one of the COs in Aliceville would tell us. Just stupid people asking them.

Despite this, he was one of the most decent COs in the place. We called him Peaches because he had some Slavic name that none of us could pronounce.

When we return to Lilli’s, I try on the suits and I must admit that it feels pretty incredible. I haven’t suited up since Baltimore. Even during the trial, my attorney had me wearing a dress so I would come across as more vulnerable, more girly, not the kind of person who could shoot someone point-black in the face or stab a man twenty-seven times with a pen. The deaths were not even part of the case, but everyone in the courtroom had heard about them, so my attorney wanted to put some distance between me and the bodies.

Didn’t help much. Matter of fact, it hurt me because I didn’t appear credible when I tried to explain away the conspiracy charge as a means to maintain my cover. It’s hard to come across as professional when it looks like you’re there as part of some civics class field trip. I should’ve worn a suit.

But these suits — Lilli’s suits — these are not the drab sacks I would wear when I was in the Bureau, the bu-suits that you buy off the rack. These wear like money and I can feel myself standing a little taller because of them. I leave wearing the pinstripe trousers with an orange long-sleeve top which I would’ve thought horrifying but actually looks pretty damned good on me. I never knew it was my color, but Lilli says that Autumns are certainly my color given the soft tone of your skin and the lovely warmth of your beautiful eyes. Jesus, I am really getting to like her.

The only thing missing is the weight of my service weapon on my hip, feeling that solid bulk riding over the side of my butt. Very comforting.

Mia then finds me a pair of stylish flats in a shop up the street. Over four hundred euros, too much, but she insists. They look good and, more importantly, they’re great for running.

In case we need to run, she says with a sly smile.

Okay. Now we’re getting into the game.

“Who’s the little girl?”

The guy tries to act cool but it only makes him seem all the more dreadful. The stylishly hip horn-rimmed glasses, the muss of short brown hair that probably requires hours of fussing, the facial shadow, the lack of socks, the silk suit, and these shockingly green eyes that I’m pretty certain are nothing more than tinted contacts.

Holy fuck, would Byrone have some fun with this guy. He hated posers.

“This woman is a friend,” Mia tells him. They are speaking Dutch but I can understand the words well enough. And her tone — it is loud and clear.

The man is plainly taken aback by the indignation in Mia’s voice. He wants something, or needs something, and Mia is the only person who can provide it, so he immediately backpedals, makes a show of amends to Mia. I watch as I sit comfortably in the uncomfortable chair of an outdoor café. The sun has already dropped behind the buildings that line the canal — the passing tour boats now carry more couples than families. I’m wearing the sunglasses Mia insisted on buying for me, spotted at a kiosk on our way there. She thought I looked so cute in them, so I guess this guy couldn’t call me a girl, but she can. Yes, it’s condescending but I still need her attention, so whatever she wants, I’ll allow.

<

br /> Besides, I looked in the mirror at the glasses, the scar, and I’m damned cute in a hard-ass sort of way.

They continue to talk for nearly an hour, as the lights along the wandelplaats flicker to life and shops become busy with the surge of locals making their way home at the end of their day. The only thing I understand from the conversation is that this guy is suppose to provide Mia with some amount of information about someone else, and only then will she give him what he wants. He says he’s close but he needs more time. She says that he has three days, that she and I are heading up to Copenhagen and that she wants to hear from him within the next three days.

I had been to Copenhagen once before, when I was in the Army with the 66th MI. I traveled up to Denmark with Staff Sergeant Williams to deliver a box full of documents in one of those puke-green POSes that screamed government issue, and that evening, we found ourselves in a gay bar by happenstance. It was fun and all — the people were really nice — but so many of them were offering free drinks to our American friends that we finished the night plastered and ended up having sex after we staggered back to the TDY barracks. I think mostly to prove to ourselves, and one another, that while it was amusing, that bar was not our kind of bar. Not my finest hour, amid so many unfine hours.

After we leave Hipster Man at the café, I ask Mia why we’re going to Copenhagen.

She smiles. She says she has some friends she wants me to meet.

7

Copenhagen — Lund

Anna and Iben almost throw themselves on top of Mia, screaming and giggling and swaying her back and forth as if she’s some long-lost, never-forgotten, forever-adored rag doll. If we were all in our twenties or thirties, I’m pretty sure Anna is the type to leap into Mia’s arms and wrap her legs around her. In their fifties, there’s enthusiasm, but it’s tempered by the desire not to hurt themselves. Still, it’s the kind of public arrival that I dream about.

When Mia introduces me, they’re both still aglow with excitement and Anna has to hug me and like a stupid, foolish child, I start to cry. It causes everyone to become concerned, Iben to chastise her sister, and put a damper on the whole thing.

Yeah, that’s me.

“Oh, bokkie. What’s the matter?” Mia asks, wrapping me in her arms. I can’t talk. I bury my face into her shoulder and bawl. She tells the sisters that I’m tired, that’s all, as she rocks me gently.

God, I feel like history’s biggest freakin’ loser. Why am I crying again? Before this trip, I hadn’t cried since…well, there was right after the attack, the first time I took stock of the damage done, when I was still high on a staggering amount of opiates. But that was different. That wasn’t crying for crying’s sake, that was the shock, the coming to terms with the devastation of my own body. Now, here I am again, against my will, bawling my eyes out.

Get a fucking grip!

The sisters drive us from the airport to Lund, Anna pointing out when we’re crossing over into Sweden. She’s in back with me, holding my hand and patting on it like she’s petting on a lost little puppy. It’s embarrassing, of course, and it gets on my nerves, but I don’t have the heart to ask her to stop because it seems as though she’s trying so hard to have me like her. I can only imagine what she thinks of me — a weepy, emotional little dit.

They’re Danish, Anna tells me, her and Iben, but they live in Sweden where her sister teaches at the University and she manages artwork in a small gallery. Both of their parents are artists — pretty famous among the art crowd. She tells me their names, to see whether I will recognize them, and I can only apologize. I can’t tell you the name of one artist after Leonardo DiCaprio…I mean, Leonardo da Vinci.

Was he even an artist? Didn’t he do the Mona Lisa or something? Or was that someone else?

Anyway, I can tell you the model of Glock if you handed it to me, but I don’t know shit about art.

“Mam has a painting in the SMK,” she says, pointing off in some direction while we’re still near Copenhagen. “Not that you’d ever find it. It’s off in a back corner somewhere.”

“It’s actually a destination in a pretty popular scavenger hunt at the UC,” Iben says, looking at me in the rearview mirror.

“The University in Copenhagen,” Anna explains.

“She used to have two.”

“But the other was damaged.”

“Papa,” Iben states with a snort.

“Yes, probably Papa.”

From the tone, I understand that it is a long-standing joke in their family.

“Papa’s never had a painting on display,” Anna then says. “Not in any big venue.”

“Gives him a piss.”

“Yeah, and Mam likes to remind him whenever he thinks he’s winning an argument about art.”

“Those with a piece hanging in the SMK?” Iben is imitating their mother.

“Raise my hand,” Anna finishes.

They laugh and Mia smiles patiently. She’s obviously heard this before, many times before.

Holy shit. Would they ever consider adopting a little Coloured girl?

When they released me from prison, I traveled by bus from Aliceville to Tuscaloosa and on to Birmingham, where I hopped the Crescent 20 to Baltimore Penn Station. It was a long-as-fuck ride but after so much practice at sitting quietly in place, it was endurable. At least it had changing scenery outside a window, which most everyone seemed to disregard. Everyone except for me and the small children.

It was the station that gave me the most trouble. I’ve been in the Bal-Penn many times. It was where I caught the train home for the holidays. Being back reminded me of the life that I once had, when I was on the other side, the side of the good guys, and I was someone else — back when Mom and Dad were still proud of me. (Though Mom really believed that I was trying to make some sort of statement about her when I joined the Bureau. A knock against her profession in academia, her passion for protest and her speaking out against injustice. In truth, I joined the Bureau because I had a crush on a guy in the Army who talked about joining when he ETSed. I made it in, he didn’t.) Now, legally, I couldn’t even visit my folks because they had moved to Montreal while I was away at Aliceville.

I considered calling some of the people I knew at the Windsor Mill office, though I wasn’t sure how many of them were still around. Of course, it was a stupid idea anyway because it was problematic for them to be seen with me. I was persona non grata among everyone in the Bureau — a pariah. Any letters of recommendation from them were really going to suck. And it was there, while I waited for my next train, the one to Boston, that it dawned on me that I was beginning yet another phase in my life. Here I was again, starting over, only this time, I was starting from way, way in the back. Shit, I didn’t even have my socks on when they fired the starting gun.

Our arrival at the Copenhagen airport brought back memories of my arrival at South Station. When the sisters spotted us — that is, when they spotted Mia — they reacted in the way I was hoping Tonya would’ve done. Holy shit, if she had only shown me one moment of kindness or warmth or empathy, I’m pretty sure I would be a much better person right now. Instead, she made me even more bitter and left me feeling even more alone, which…. Well, actually, which led to my being there in Copenhagen, I guess.

In her defense, she did get the schedule completely fucked up and when she arrived, she did have my two little nieces in tow — Rama by the hand, almost being swept off her feet, and little Mariame on her hip. She didn’t even introduce me to the children. She was frazzled, going through the divorce. How great it must’ve been for her, to meet her sister at the station, the one recently released from prison.

Still, Naddie would’ve at least given me a hug.

“Goddammit! I knew it!”

Anna stabs her finger at Iben repeatedly in a form of I told you so and gives her an expression of I-am-right-and-you-are-so-wrong that is the kind of expression that can be passed only between sisters.

Iben makes a show of disregardi

ng her, trying to remain focused on me, trying to smile warmly at me, while telling me with her eyes See the shit I have to put up with.

I know how you feel. I’ve been on the receiving end.

Me and my sisters were like this once, during the times we got along. (Though, before I become too enthusiastic with rewriting myself into a happy, joyful childhood, I must point out that Tonya would’ve already corrected me with “my sisters and I.”) It’s what happens between all sisters probably — the little competitions that are so transient yet so important to your shared history that someone is always keeping the score, has been keeping score all of your lives. Tonya kept the score for us, not that Naddie or I asked her to, but she felt the job too important to allow it to be screwed up by either of us.

It’s odd, though, seeing this behavior between sisters in their fifties. Will Tonya, Naddie, and I end up like this, if we’re still talking? I imagined that we’d all three grow into dignified women, like Mom, except that whenever I relate stories about Mom to anyone else, they always did one of two things: laughed and said that our Mom sounded great, which meant that they thought she sounded like a loon, or they gave me that look of understanding and a touch of Oh, you poor dear.

Really, thinking back to the way she was, Mom was pretty much a nut at home. An intense, energetic nut, that is, not the dark, depressed one Ma ended up becoming.

Am I responsible for this kind of behavior?

“There’s a wiki page about it,” I tell them. There’s no use hiding it since Mia already knows.

Iben and Anna stop what they’re doing — freeze — and blink at me for a moment, as though they each need time to think things through before making their first move. Otherwise, they might give their game away to the other too early. Then, without another word, they both clap their wine glasses down on the table, pull phones from their pockets, and frantically begin searching, which causes Anna to giggle. As the younger of the two, she’s the most frenetic.

Zwerfster Chic

Zwerfster Chic