- Home

- Billie Kelgren

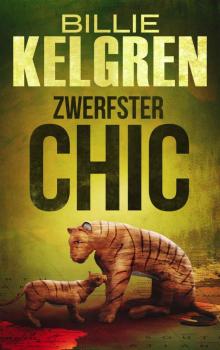

Zwerfster Chic Page 5

Zwerfster Chic Read online

Page 5

I was only nine and it was the first time I had traveled anywhere by plane. I was going from the bottom of the world to the top of the world and across a whole ocean.

I wished I had one of those Pan Am bags.

When we turn back at the gate, I fall behind as Mia and Maggie climb the rutted road heading up to the farmhouse. It’s cold and damp, weighing down my hair so that it loses its spring. The coat I wear now smells of wet sheep, which smells much worse than wet dog. I’m a mongrel and the self-pity drips off of me down onto the ground.

“Bokkie.”

I look up, pulling the hair to one side so I can see. Mia has stopped, waiting for me, holding out her hand to encourage me forward. Maggie is watching, leaning back so she can see around Mia as I hop up the road to catch up. When I reach them, Mia wraps her arm around me and holds me close to her for the rest of the way back.

Ha! Ha! Fuck you, Maggie!

Everything that I owned was stuffed into the small, floral-print canvas bag: my clothes, a picture book, a photo of Ma taken before I was born, and a set of painted animals carved from wood, all of them pairs of mother and child — donkey, elephant, giraffe, and tiger. These were my favorite toys, though I rarely played with them anymore because I was becoming too old, but I would not leave them behind.

The bag was given to me by the Old Man, whom I met for the first time after Ma was dead. He said the bag belonged to Ma when she was a small girl, that she used it to carry her dolls and toy horses and sometimes a book when they journeyed out to the family farm somewhere on the veldt. The farm, he said, had been in the family since they first came to the continent in the early 1800s. I wished I could go see the farm, because Ma had played there, but then it was only for the family, so I figured I wasn’t allowed.

The Old Man said that he was Ma’s father, but he never said anything about that making me his granddaughter.

I was brought to the home of the Old Man after I carefully climbed down the steep steps to the liquor store to tell Mnr. and Mev. Kuiper, the owners, that I had found Ma dead. Men took Ma’s body away and I had to stay in the room for another couple of days before someone who worked for the Old Man came to the door and told me that I was leaving. I took the animals from the shoebox underneath the bed and put them into a paper sack so that the man would pack them along with the other things that we took with us. We left almost everything else behind. He then put me onto a crowded train, where everyone had skin darker than mine, and when I reached the other end, I was put into the back of a pickup truck, where I rode among crates, going so far into the countryside that it was dark when we finally came to a stop. I had fallen asleep. They fed me in a small kitchen — I had only eaten three little rolls of bread in the days following Ma’s death — and then put me to bed in a small, windowless room where I woke up the next morning to the sound of servants being busy.

I was taken out back, put into a steel tub full of cold water, and scrubbed by a dark-skinned woman until all my own skin came off. I was given new underwear, a new dress, and a new pair of shoes, then taken to see the Old Man in his office in the biggest of the houses. As I waited outside the door, in a chair so high that my feet swayed over the floor, I craned my neck to look about, trying to see what I could see. There were people, most darker than me, who seemed to move about quietly, busy with work, and people who were all lighter than me, like Ma, who were laughing and talking and seeming to take their time about things.

I remember hearing Ma tell the women in the park that I was the daughter of her favorite servant, back when she grew up in Cape Town. The servant died, leaving me an orphan, and she took me to raise as her own because Ma said she felt that she owed her that much. She had made a promise. That’s why I loved Ma so much, because she gave up everything for me. She would tell me what it was like, growing up where she grew up, as we lay together in bed with me in her arms and she softly petting my hair. She would cry sometimes because she missed her home so much, but that meant she loved me more than anything. I loved her unconditionally, which is how I thought it should be between a mother and daughter, how it would’ve been with my real mother.

What did I know?

We borrow Maggie’s car for a trip into Dundalk, Mia saying she needs to drop off a package at the postal service. Maggie wants to come along but it’s clear that Mia has timed the request so that Maggie is in the middle of working the flock with Uncle Brick, unable to get away. Besides, Mia tells her, we’re not doing anything of value while she’s busy in the fields, so this seems to be the best time for us to go.

After we drop off a thick envelope in town, we pull onto a motorway. I point out that we had not taken this road on the way there and that’s when Mia tells me that we’re heading somewhere else, that we’re not going back to the farm. I mention our bags and she tells me that they’re in the back, behind the seat. About an hour and a half later later, as we’re pulling into the terminal, she tells me about the ferry that’ll take us to Cairnryan.

I have to give Mia this much: she never said to Maggie that we’d be back.

Sometime later, I wake with a start — snorting, I think, as I blink and look around, trying to remember where I am. Mia shushes me and I settle back down, resting my head on her lap again as I wait for my brain to catch up. We’re on the ferry, crossing the Irish Sea, and I’m laying on a bench at one of those laminate tables in the snack area. She’s looking off at something in the distance as her hand unconsciously strokes my hair.

“Maggie just recently lost her mother,” she tells me. I don’t say anything so Mia continues on about how Maggie’s mother had been a heroin addict when the girl was a child, never really a part of Maggie’s life. “She’s never had a chance to cry about it. She’s always too busy taking care of the others and never took the time to take care of herself. Maggie hates her mother and she just needed someone to hold her and tell her it’s okay to cry.”

Maggie’s mother died last year, when Maggie was twenty-two. Try finding your dead Ma at nine.

Not that I’m being competitive or anything.

We drive across the bottom corner of Scotland and along the top edge of England to another ferry terminal over on the east coast, stopping as we come into Newcastle to find a DHL where Mia picks up another heavy envelope much like the one we had dropped off. She hands it to me as she slides back into the car and tells me to open it. Inside is my South African passport, and inside that is page after page of visas. I’m stunned, asking her if this was what she had sent out that morning. She’s amused.

“I took that off you when we first arrived in Dublin.”

How long ago was that? A week? Two weeks? It’s the day before yesterday, but it feels like we’ve been gone for a month.

She also sends out an express letter to Maggie with instructions on where to find the car, parked in the lot of the ferry terminal with the keys up under the seat. I ask her how she thinks Maggie will react to our taking it and never returning and Mia mentions that she included a couple of hundred euros in the envelope. That doesn’t seem like much, given the trouble Maggie will have to go through, but Mia says that it will be enough.

“I want her to feel that we owe her something. She’ll be eager to see us again and you never know when you might need someone like that.”

Mom was pissed at the Old Man, back before I called her Mom, and I thought she was angry with me, so I hid behind Dad’s legs. He had met me at Logan, in Terminal E, and seemed to tower over me as he read the note that he found pinned to my dress. He scared me at first, being so tall and so dark. I thought he was another servant, sent to fetch me, but he seemed to regard me awkwardly, glancing about at the other passengers coming up the narrow gangway as though he had made a mistake. I was the wrong girl for him to pick up and now he was looking for whomever I belonged to.

He then tried to speak to me, but I didn’t understand the words. I mean, I had heard English often enough back home, in Die Baai, but I didn’t know that this stuff he was spea

king was the same. It didn’t even sound anything close to it. He finally called to the passing people and eventually a young Coloured couple stopped to offer help. As the men spoke, the young woman knelt down and smiled at me kindly. Maybe these were my new parents, not thinking that if they were, we would’ve met when we first boarded the flight.

What can I say? I was nine and I was baffled. My life was pretty much a mess.

The Coloured man told me that I was to go with the Black man. I asked for the Black man’s name and after some quick words, the Coloured man said that I was to call him “Dad,” because he was my father. I stood there, looking up at the two of them, and then as if someone had flipped a switch, tears started rolling down my cheeks. I didn’t even make a sound. I was too bewildered to know what sound to make, if there’s a particular sound for an occasion like that.

The woman made a sound, though, and took me in her arms and told me not to cry, like Ma would’ve done, and I wanted to be with her. I asked if she knew Ma, if she was with Ma when she was young and lived at the big house with the Old Man. She wasn’t understanding, but I believed she was, in fact, my real mother. Maybe something had happened to her, and now she no longer recognized me.

She held me and sang to me in words I could understand until I calmed down, at which point she and the Coloured man said that they had to leave me and I started to cry again. The man led her away because she was crying herself and maybe she was beginning to remember me but after a few moments they disappeared into the passing crowds.

Poor Dad. All he could do was crouch down in front of me, put his hands on my shoulders, and try to smile as though he wasn’t as scared and confused as I was. He then took me by the hand, my floral bag in the other, and led me on the bizarre journey through what I now know was the MBTA to the place where I found myself hiding behind his legs to avoid the angry gaze of the fearsome dark woman.

She wasn’t angry with me, of course. She had just read the note written by the Old Man, given to her by Dad. I never had the chance to read it myself but Mom told me many years later that the Old Man was a fucking bastard. It was the only time I ever heard her use that word.

Not “bastard.” She uses that one a lot.

She then knelt down before me, because all mothers know to do this with children, and slowly said “Bel my ‘Mom’.” I was confused, but I smiled anyway because she was telling me that she wanted to be like Ma, she wanted to look after me. I put my arms around her neck, kissed her cheek, and then held onto her as I waited to feel her hug me in return, like Ma would do. She held me, though, with her hands under my arms, so that I had to lean into her, and this became the first of our many awkward hugs.

Mom then pushed me gently away and slowly asked “Wil jy graag jou susters te ontmoet?” I just stared back at her, so she tried again, more carefully, thinking that I didn’t understand, thinking her Afrikaans was not good, but that wasn’t it. I was just surprised.

I didn’t know I had sisters! This was perfect! I had been returned to my family at long last.

It is part of our family history that, on introducing me to five-year old Tonya and two-year old Naddie, Tonya’s first words on the subject were But she’s white.

The trip across the North Sea goes over the night and though our cabin has a twin bed along with a double, I wait until Mia’s breath becomes steady and soft in the darkness and then slip in beside her, curling myself up close to the pillow. With my hand touching her back lightly, so as not to wake her, I fall asleep. My first peaceful, dreamless night in years.

6

IJmuiden — Amsterdam

Sometimes, I worry that I have some form of social blindness, that I say things without knowing I said them. My unease around other people was something I grew up with, but this belief in a possible brain malfunction began with a gray-haired lifer at the office in Baltimore. He claimed that I had publicly described one of our colleagues as “a big, round basketball” at one of our weekly meetings. Duggs was, in fact, somewhat short and round but I always kind of liked him because of the pleasant way he had of quietly smiling as he lingered in the background.

The lifer’s name was Holfmann and he never liked me because he never really liked any of the younger…. Actually, that’s not true. He was fine and friendly with some of the new agents, as long as they were male and white. Or lightly Hispanic — light enough that he couldn’t tell until you told him your last name was Gonzales or Morales. Anything else and you were only there to fill the quotas as far as he was concerned.

I was a bi-POD, obviously, being both female and black, but I made the mistake of pointing out that I was also a multi-national. I said that this made me a tri-POD and the word spread. The problem was that, without a distinct “foreign” accent, my third point of diversity was left to speculation and it was quickly rumored that I was a lesbian. I mean, the list includes race, color, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, parental status, age, mental or physical disability, and genetic information, so of course they had to leap to lesbianism since it was mostly OWFs making the distinctions and nothing makes old white guys more horntastically hopeful than the thought of a lesbian nearby. Even after I started dating Hecht, a guy two floors down that I made it through the Academy with, all I earned was a fine-tuning from lesbian to bisexual.

Though they never seem to think their own preference for young white males isn’t somewhat blatantly gay.

Anyway, Holfmann found a jamocha-flavored clit-licking split-tail threatening to his rightful place on the org chart, so he was always something of a hassle to deal with. I did my best to remain professional. Still, it kind of threw me when he told me about what I had supposedly done. It was the way he said it, the way he laughed with disbelief at my not remembering describing Duggs as the basketball. It made me wonder if I had, in fact, said those words and then somehow blanked the event from my own memory. Maybe I have some neuropsychiatric disorder, like Tourette’s. Maybe I say things out loud that I should be keeping to myself. I sometimes worry that I do, because Ma used to tell me Bokkie, you speak without a moment’s pause in your head.

But I can’t imagine myself describing Duggs as a “basketball.”

But then, maybe that’s why I never seem to have any friends.

Maybe I’m a terrible person and don’t know it. I mean, some of the most evil people think of themselves as a fairly decent sort. They even have mothers that love them.

Maybe. Maybe. Maybe.

It makes no sense, but self-doubt rarely does.

I call Bouchard as the ferry is coming into IJmuiden, when I can get a strong signal and Mia is up on deck for a last cigarette. I list on the voice message the countries for which I now have visas and tell him that I’m concerned because I have the impression that we won’t be returning anytime soon. I’m required to make a personal appearance at least once before the end of the month and even though I know that Al is handled, I want to make sure that he won’t suddenly find himself in any sort of trouble.

I also tell Bouchard that I had a chance to flip through the planner that Mia always carries with her. She never keeps anything on her phone. Everything is written down in a small Moleskine planner in a foreign language, or a code — I couldn’t tell which. She probably makes up her own language, given how easily she seems to slip from one to another.

During the journey, I was dumbfounded by how she deftly managed a dispute between a Polish couple and an Italian family in the middle of the North Sea while explaining what was going on to the flustered, Dutch-speaking attendant. It’s as though she has no language barriers at all. Bouchard had forewarned me and you can be told someone is good with languages, but this is a whole lot of something freakishly different.

I asked her, during dinner, how she learns to speak so many so easily and she said that she does not learn a language as I might understand, but simply learns new words to say the things that she already knows how to say — There are toddlers learning to speak a new language eve

ry day without much effort. It’s not that hard.

I guess. I mean, you never do hear three-year-olds talking about proper conjugation. But it’s so supremely easy for her that it makes her self-conscious, which is surprising in itself.

Mia warns me about Lilli, after calling ahead to make sure Lilli’s schedule is cleared for the day. We come directly from the ferry once it reaches IJmuiden and Mia wants two suits finished before the evening. She’s the kind of person who can make such demands and still receive welcoming kisses on arrival. The shop is tiny — maybe fifteen feet across — jammed in along a stretch of the Hooftstraat shopping district of Amsterdam among stores with names like Dior, Bulgari, and Chanel. There aren’t any shops with the name Goodwill, so it’s not the kind of street where I usually find myself.

Lilli moved to the Netherlands when she was a teenager. She’s originally from Estonia and looks like she should be spending her time being a supermodel — tall, blonde, with high, sharp cheeks, and pale blue eyes that, by instinct, you have to hate. She wears pants, a blouse, a stylish scarf, and those little non-prescription magnifying glasses down on the tip of her nose so that she has to tilt her head back to look through them. She’s a teenage boy’s fantasy of a hot teacher but she has this endearing way of looking at you that makes it feel like you’re the prettiest one in the room. Even me.

She has me on top of a small platform, facing a circular wall of mirrors, and she climbs up there with me and it’s as though she’s molding the loose, shapeless material right to my body. Hands are everywhere — smoothing, pulling, caressing, tugging, while pins tuck, chalk marks, and clamps hold. I’ve had cavity searches performed by moody COs that were less invasive. Her fingers glide up under the coat and she takes my boobs in her hands — well, what’s left of them — and asks me the type of bra I’m wearing, tsking when I tell her it’s a sports bra. In Dutch, over her shoulder, she reprimands Mia for not teaching me how to dress properly.

Zwerfster Chic

Zwerfster Chic